By Katie Musser Joy, For The Mountain Times

My Father, Lloyd Alrick Musser, passed away on March 1, 2025, but his passion for telling the story of Mt. Hood, its people and history, lives on every corner of this mountain. It’s hard to keep my words to a minimum when speaking about the greatest Father, and the greatest man, I have ever known. He was endlessly kind, steadfastly trustworthy, and a man whose word you could take to the bank. He loved his family and friends with quiet strength and unwavering devotion. I could write a book about each decade of his life and still have stories left to tell.

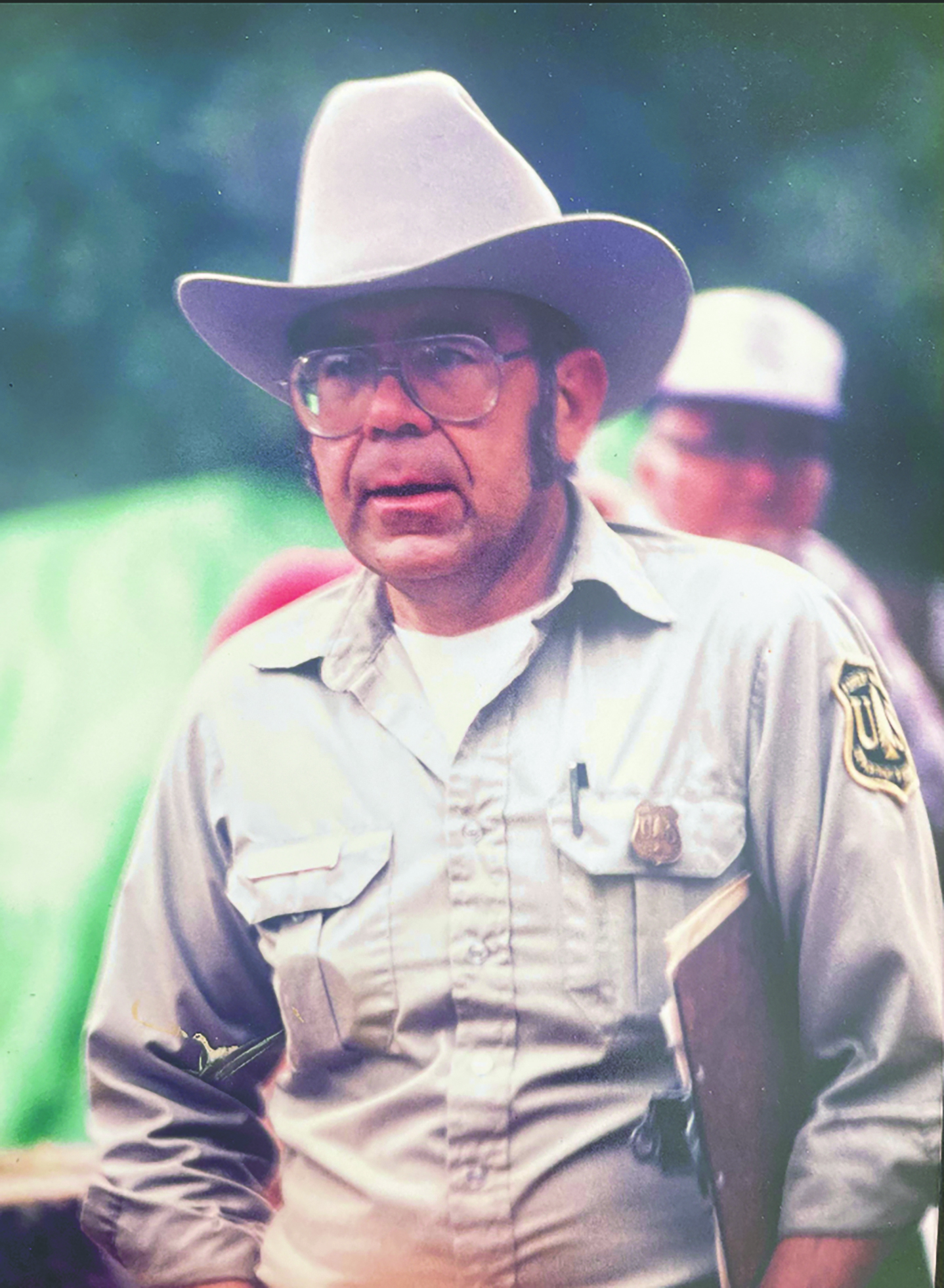

Most people knew my dad as the Mt. Hood Cultural Center and Museum curator, where he volunteered tirelessly for over 25 years. He was the man who could tell you the story behind every photo on the wall, every artifact on display, and every person who made Mt. Hood what it is today. But I want to share about the whole man, not just the curator, because my Dad’s life was much more than what people saw at the museum.

Born on September 9, 1942, in Ohio, Dad always had a deep love for history and the outdoors. After ranger school and a brief time in the armed forces, stationed in Germany, he eventually found his way west, where he discovered his true home on Mt. Hood. He spent decades working for the U.S. Forest Service, helping protect and manage the lands he loved so deeply.

In 1998, he took on the role of curator at the Mt. Hood Museum. What started as a small volunteer project quickly became his life’s work. He built the collection piece by piece, treating every artifact as a treasure and every donor as a friend.

My Dad was especially passionate about preserving the legacy of Henry Steiner and his iconic cabins. He made it his mission to protect these historic homes, organizing tours and educating visitors about their craftsmanship and cultural significance. I can still hear him marveling at the hand-hewn logs and the artistry that went into every stone fireplace. To him, these cabins weren’t just buildings — they were part of a living history.

Many people also knew my Dad through his writing. For years, he contributed historical articles to The Mountain Times, sharing stories about Timberline Lodge, the early days of skiing, the pioneers who settled here and the Native peoples whose stewardship shaped this land long before any of us arrived. One of his most-read pieces was “A Short History of Timberline Lodge,” in which he detailed the lodge’s construction and its role as a Works Progress Administration project during the Great Depression. He was endlessly proud of that story, and even prouder of the lodge itself.

But there’s a chapter of his story that isn’t always told. He was a Father, a Grandfather, and a friend. He loved a good story, a strong cup of coffee, and a long hike in the woods. He never missed a chance to watch the sun rise or set over Mt. Hood. His passion wasn’t just about history; it was about connection. Connection to people, to place, and to purpose.

The final story, from Lloyd

Before my Father passed, he wrote the story of how our lives started and his time in Juniper Flats to give to me at Christmas 2024. I would like to share with you a shortened version of his story in his words,

“Mo and I were married in September 1972 at Timberline Lodge. We then skied down the Glade trail to our cabin in Government Camp where we had settled. It made sense to settle here as I worked at Bear Springs Ranger Station, and Mo was selling real estate in Rhododendron. We bought a little 1937 cabin on Blossom Trail and fixed it up ourselves — cut our own logs, stacked flat rocks for the fireplace, and even added a rental apartment for extra income. We heated with wood, cut ten cords a year, grew a few greens in raised beds, and baked everything from scratch. Life was simple but good.

Government Camp, back then, was a quiet ski village, 200 cabins, a store, a couple of restaurants, and a tavern. In winter, it filled with skiers; the rest of the year, maybe a hundred folks stuck around. We’d ride the shuttle to Timberline Lodge, ski all day, then coast 3.5 miles down the Glade Trail right to our door. The downside? When snow piled up, we parked down the hill and hiked home with groceries in hand. By June 1977, when we still couldn’t drive to the house because of lingering snow, we figured it was time for a change.

We bought 40 acres in Pine Grove — half pasture, half forest — with a stunning view of Mount Hood. No water, no power, no guarantees. But we were young and optimistic. We decided if we found water, we’d stay and build. If not, we’d sell. We hired a driller. On the fourth day, just as we hit 500 feet, the drill’s sound changed. Water! Five gallons a minute. We drilled a little deeper and got twenty. We had our well — and our green light.

Mo designed the house herself. Evans Products turned her sketches into certified plans, with all the materials delivered in stages. It wasn’t a prefab, but a true do-it-yourself home. In May and June of 1978, everything changed. Mo was pregnant, due February 1979, we signed the house contract, and the Forest Service offered me a deal I could not refuse. I was selected for a slot in a college masters degree program starting in the fall of 1978. It was an accelerated course in silviculture at the University of Montana. The program changed my life forever and I still practice the techniques taught in that short course 44 years later.

Meanwhile, back at Rocky Top Ranch — as we called it, thanks to the rocky soil — things moved fast. In a panic, we had just started installing roof shingles when it snowed about 2 feet of light powder snow. We hired some men from Government Camp to work on roofing. They came each day, shoveled snow from the area and laid shingles. With freezing weather on the weekend, a group of employees from Bear Springs Ranger District would help us as long as the beer and the food lasted. With this extra help, we managed to get the building closed in.

Mo and I were living in a 20-foot travel trailer. It was crowded with us and our two golden retrievers. We made the move from the trailer to the new home on Mother’s Day in May 1979. The new house was crude, but it had electricity, running water, and a functioning bathroom.

It was time to do the landscaping. The surface of the area was covered with softball to basketball size rocks. We picked rocks from about 2 acres for our lawn and large garden. We’d use the rocks to build a retaining wall. It was during that project that we started referring to our place as Rocky Top Ranch.

Over the next few years, we focused on our careers and the garden. I finished my thesis, became a certified silviculturist, and took on the job of prescribing all timber harvesting for the ranger district. A few years later, I was honored with the Department of Agriculture’s Superior Service Award, which came with a little cash and a family trip to Washington, D.C.

Back at the homestead, Mo and I grew just about everything that would take to Oregon soil — strawberries, raspberries, grapes, even watermelons and cantaloupes. We had asparagus beds and rows of vegetables from carrots to zucchini. But growing it was only half the job; under the tutelage of her mom, Pat, and Grandma Albie West, Mo became a master at preserving. She canned, froze, and dried everything, even turning out homemade sauerkraut and pickles. Every year, we canned at least 100 quarts of tomatoes alone.

Katie’s life was good the years we lived at Rocky Top Ranch. Grandparents visited often, she had dogs, kittens, some chickens, and her first pony to play with. The best thing going on for kids living in rural areas is 4H. She was eight years old when she joined the Juniper Flats 4H club. She showed lambs, pigs, horses and even did sewing in 4-H.

When Katie went to Maupin Grade School Mo started teaching there. Life was good for me during these years. I did not know it then, but within a few years, my lifestyle, my family’s life, and everyone involved with the timber industry would be changed drastically. A common, but seldom seen Spotted Owl was listed as endangered. This bird was found throughout the forests of Oregon, Washington, and northern California. The environmentalists and the court system shut down most timber harvesting on national forests. Logging companies, sawmills, even the Forest Service started downsizing and closing offices. People in rural areas associated with the timber industry began relocating to find employment. Coincidentally, Mo had decided after being a schoolteacher for 13 years, that if she wanted to advance in her career, she needed a master’s degree. Katie and Mo moved to Portland to stay with my mother-in-law while I was to remain at the ranch and try my best to negotiate the political situation between the Forest Service and the environmentalists. It soon became evident that in the near future, Bear Springs Ranger District and the Barlow District would be closed or combined. due to the moratorium on timber harvesting to protect the Spotted Owl. To protect my job, we needed to move and sell the ranch.

My plan had been to work six more years and then retire and be a gentleman rancher on Rocky Top Ranch, but I decided it would be best if I got a job in Portland. By this point, Mo wanted to pursue her PhD. I made a phone call to my friend at the Forest Service regional office in Portland and let them know my situation. Within a week I had an offer I could not refuse. While my office was in Portland. I often traveled to all 21 National Forests in Oregon and Washington. My dream of retirement at Rocky Top Ranch was gone, but in the end, the alternative turned out better for everyone. It was a rewarding experience, developing a fully functional hobby ranch from undeveloped land with no improvements at the beginning. Mo finished her doctorate and began teaching at Willamette University, later to get tenure as a Director of the School of Education.

I am thankful for the time living in the area when the population and local economy of Juniper Flats was at its peak. I had a good career for 25 years at Bear Springs Ranger District and lived 14 years on Rocky Top Ranch in Pine Grove on Juniper Flats in Wasco County, Oregon.”

My dad’s story may have ended there, in his words, but the life he built didn’t stop on that page. So I’ll do my best to finish it for him.

Not long after, he retired from the Forest Service at age 55. My Mom followed soon after, and together they stepped into a new season of life. They embraced the freedom they had earned, traveling the world hand in hand. They explored the wild beauty of Alaska, wandered through the old-world charm of Europe, and cruised to places they had long dreamed of seeing, always choosing small ships with small groups, just the way they liked it. They rafted down the Snake River, strolled along Oregon’s beaches, and found joy in the simple adventures close to home. No matter where their travels took them, Mt. Hood remained their compass. They spent more and more time at their cabin on the mountain, where they were happiest.

My mom joined the Skiyente Ski Club, while my dad devoted himself to preserving the mountain’s history. He was instrumental in founding the Mt. Hood Cultural Center and Museum, pouring his knowledge and energy into creating a place that would safeguard the stories he loved for generations to come.

Eventually, they sold their home on Sauvie Island and moved to Happy Valley, wanting to be closer to Mt. Hood, and closer to me. I was blessed to live just two miles away from them for the last eleven years of their lives. During that time, they were irreplaceable participants in my sons’ childhoods. My Dad took them on hikes, led them through museums all over Oregon, taught them how to build campfires and whittle sticks, and, of course, shared stories from the past that brought history to life. My Mom loved reading with them, playing games, and taking them on fun little adventures.

They never missed a birthday, a soccer game, a school performance, or a holiday. And my dad always thoughtfully showed up at my door with a home-cooked meal after a long workday, somehow knowing exactly what I needed before I could say a word. We were always connected like that. More often than not, one of us would pick up the phone to call, only to find the other was already dialing. We used to joke that we shared the same wavelength, a sort of unspoken connection that never really needed words.

My Dad spent his life telling the stories of others. Now it’s our turn to tell his:

The story of Lloyd Musser. Forest ranger, Curator, Historian, Steward of Mt. Hood.

And above all else, my Dad. My parents shared a storybook love, the kind you rarely witness and never forget. Over the years, they became inseparable, two souls moving through life as one. They were best friends, constant companions, and the love of each other’s lives. When my Mom passed, a part of my Dad went with her. And just seven months later, he left to join her in Heaven, because he couldn’t stay here without her. I find it beautifully fitting, even romantic, that he passed on Ski the Glade Day, the annual fundraiser he started for the museum. After all, he and my mom skied the Glade Trail together on their wedding day. I like to think that, on that last day, he simply decided it was time to go skiing with her again.

Thank you for reading my Dad’s stories all these years in the Mountain Times, also for loving my parents and allowing them to love you.

We will be celebrating both of their lives together, as it should be, in July at Timberline Lodge. Details will be shared soon via Facebook and the Mt Hood Museum. In lieu of flowers, we kindly ask that donations be made to the Mt. Hood Cultural Center and Museum, so his legacy of education and preservation can continue.