By Robert Matsumura

The Mountain Times

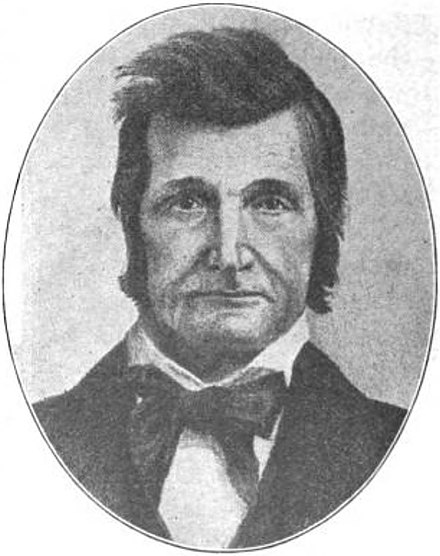

Imagine starting out from Independence, Missouri, crossing the Great Plains by wagon train, and after months of laborious toil finally reaching Oregon, only to find yourself hostage to geography and greed. Such was the case for fifty-three-year-old Samuel Kimbrough Barlow, a pioneer from Illinois who in 1845 led a wagon train across the continent only to find his family and fellow settlers stalled in the Dalles, Oregon confronted by an intolerable situation.

For thousands of pioneers traversing the Oregon Trail, reaching Oregon’s majestic, snow-capped Mount Hood shimmering in the distance was a welcome sight. After a grueling cross-country journey characterized by brutal hardship, severe weather, and, not infrequently, loss of life (it is estimated that the journey claimed 1 in 10 pioneers along the way), the elation turned to despair when upon reaching the mountain itself, this beautiful symbol of hope and promise proved a massive barrier to their ultimate destination — the fertile Willamette Valley. At that point in time, Mount Hood and the Cascade Range were impassable obstacles barring entrance to the coveted western part of the state.

As roads did not yet exist through the mountain passes, the only route to travel to Western Oregon was the Columbia River. It was at the Dalles that wagon trains from the East came to a grinding halt. Those who had survived the 2000-mile journey on the Oregon Trail found themselves languishing in the riverside town — unable to proceed any further by wagon due to the mountains — and at the mercy of avaricious barge operators charging exorbitant fees to transport their wagons down river to Oregon City. As barge operators only transported the wagons on the barges, the pioneers themselves were forced to proceed on foot along the river bank to reach their destination.

Barlow, a wagon master (those who led the wagon trains), deemed the situation unacceptable. Refusing to pay the rapacious prices demanded by the barge operators, he set out to blaze a road around Mount Hood to the Willamette Valley. In September 1845 Barlow led his wagon train along an old trail used by local indigenous tribes running along the southern slope of Mount Hood to Willamette Falls in Oregon City. Barlow was later joined by another wagon master, Joel Palmer, and his train. Palmer had learned of Barlow’s attempt to reach the Willamette Valley via this route and wished to join in the venture. By winter, the two men and their wagon trains were successful in blazing a road through the forests and foothills of Mount Hood all the way to Oregon City, thereby creating the first overland route through the Cascade Mountains to the Willamette Valley.

Shortly thereafter, Barlow petitioned Oregon’s provisional legislature for a charter to build a toll road along the route he had just cleared. The charter was approved for the Mount Hood Toll Road, which was popularly known as the Barlow Road. Taking on Phillip Foster (a farmer residing near Eagle Creek) as a business partner, Barlow, with $4000 financing from Foster, hired a team of forty men who completed the road in 1846. Laurel Hill proved the most challenging part of the new road due to its steep grade which required ropes to lower wagons down the section one at a time. Known by pioneers as the Laurel Hill Chute, this precarious stretch gained a reputation as being the most dangerous section of the Oregon Trail.

The Barlow Road was a one-way, east-west toll road that charged five dollars per wagon and ten cents a head for livestock. It is estimated that 25 percent of all immigrants to Oregon arrived via the Barlow Road. Records indicate that in its first year of operation the Barlow Road serviced 1000 emigrants and 145 wagons through its five toll gates. Barlow’s charter provided for a 2-year concession after which time Barlow and Foster dissolved their partnership, opting out of what had proved to be a relatively unprofitable venture. For the next seventy years the road was operated by private owners with mixed results, eventually ending up in the possession of state senator George W. Joseph, who bequeathed the road to the state of Oregon in 1919.

The construction of the Mount Hood Highway (Hwy 26) in the 1920s incorporated the majority of the Barlow Road, though a few sections still survive. Old wagon ruts can still be found at Laurel Hill, Barlow Creek and Pioneer Woman’s Grave. The first tollgate was originally located at Gate Creek near Wamic, Oregon. The second tollgate, known as the “Lower Crossing,” resided along the Sandy River. The third tollgate was at today’s Summit Meadows where wagons would rest and prepare to descend the treacherous Laurel Hill. The fourth tollgate was located west of Laurel Hill where the wagons regrouped after their descent. A log cabin, referred to as the Mountain House, was constructed here to accommodate the weary travelers. The site itself was known as the “Meeting Rocks.” In 1883 the fifth and final tollgate was constructed near the present day community of Rhododendron and remained in operation until 1918. A tollgate replica still stands today commemorating this location.

National Historic Trail status was granted to the Oregon Trail and the Barlow Road in 1978. In 1992 the Barlow Road earned additional protection and distinction when it was granted Historic District status and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today the legacy of the Barlow Road lives on through historic sites and even commercial establishments. Restaurants such as the Tollgate Inn in Sandy, the Barlow Trail Roadhouse in Welches, and the Tollgate campground in Rhododendron all pay homage to this vital part of our nation’s past. And last but not least is the town of Barlow itself, residing a mile east of Oregon City and named for William Barlow, Samuel’s son. While the Barlow Road may have faded into history, the memory of it is alive and well!